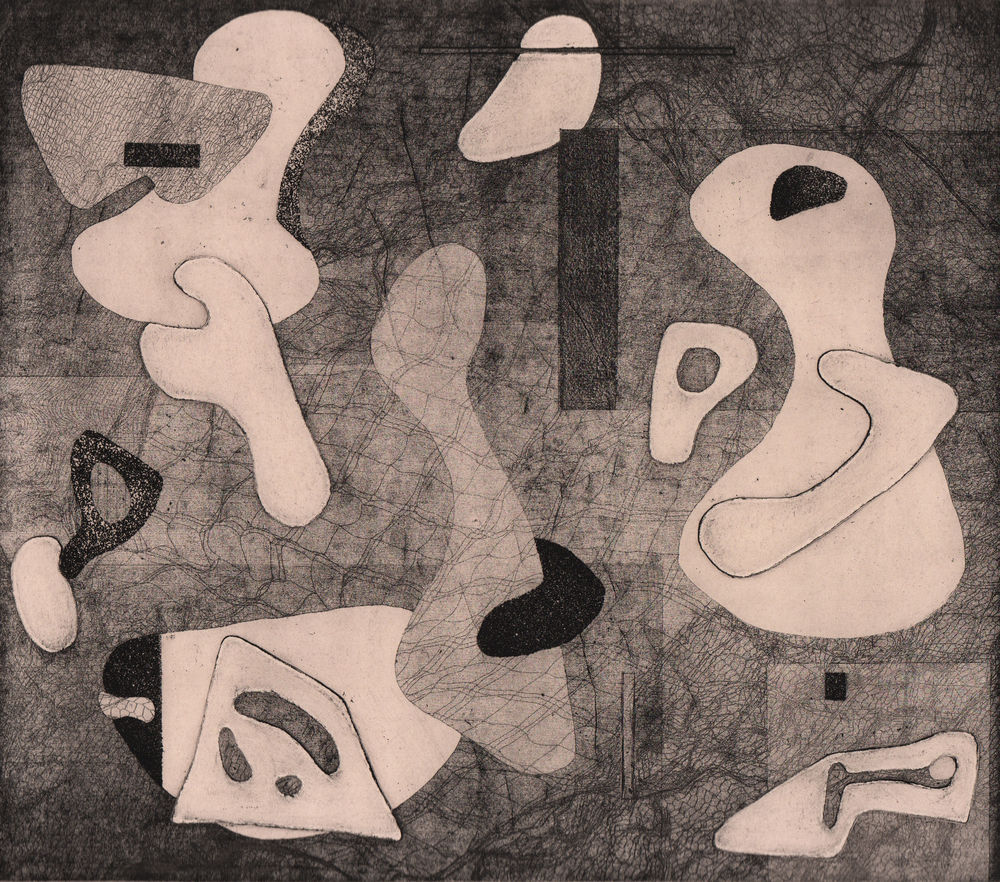

Alice Trumbull Mason, born 1904 in Litchfield, Connecticut, enjoyed the distinct benefit of growing up in a creative family. Her mother Anne Train Trumbull (1865-1930) painted before having children, and her father was a descendant of John Trumbull (1756-1843), the great American history painter. Like her mother before her, Mason spent a significant time in Europe during her youth absorbing the cultural and artistic past. Her first exposure to artistic training occurred in the early 1920s, when Mason studied painting at the British Academy, learned the history of art, sketched local masterpieces and nearby landscapes, and wrote poetry. Between roughly 1924 and 1928, Mason enrolled in life class of the realist painter Charles W. Hawthorne (1872-1930) at the National Academy of Design. Hawthorne seems to have referred Mason to study with one of his former students, Arshile Gorky (1904-1948), who was then teaching at the Grand Central School of Art, and Mason learned through Gorky to incorporate synthetic cubism into her still lives as early as 1929. Her career slowed down in the early 1930s with her marriage to Warwood Mason and the births of two children in 1932 and 1933, but she remained active in the literary world corresponding with William Carlos Williams and Gertrude Stein. Mason restarted her painting career in 1935, becoming a founding member of the Associated Abstract Artists group and having solo shows at the Museum of Living Art (1942) and Rose Fried’s Pinacotheca (1948). Mason came to Atelier 17 once it had moved down to its Eight Street location, probably after meeting Hayter and other workshop members at one of the popular social hangouts in the Village. Her first etchings, produced in 1945, allowed her to develop further what she called her “architectural” abstraction by exploring techniques like pressing fabric and other textures into soft ground etching. Working at Atelier 17 also opened up many opportunities for Mason to expand her professional network and distribute nonobjective prints more widely than she could her paintings. She continued printing color woodcuts until a few years before her death in 1971. Mason’s commitment to geometric abstraction never flagged, and her color woodcuts further developed her experimentation with biomorphic shapes across textures, colors, and dimensional planes. Mason installed a press in her uptown studio, a long-term loan from fellow Atelier 17 member Letterio Calapai (1902–1993), which enabled her to print the woodcuts more efficiently. Painting remained important to Mason, but these woodcuts were instrumental to maintaining the circulation of her name within national and international exhibitions of American modernist printmaking.

We thank Christina Weyl for this biographical information.