In 1936, after winning the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Purchase Prize for her sculpture Young Woman (1935–36) and completing a private sculpture commission for Saint Joseph Catholic Church in Sacramento, California, she was awarded a Phelan Traveling Fellowship to study abroad. She traveled throughout Austria, Germany, Italy, and France, eventually settling down in Paris to a little room on the Impasse de Rouét. Producing sculpture was difficult there, as she had no place to cut stone out of doors and dropping temperatures made that option impracticable in any case. She instead joined friends at Atelier 17, the intaglio print workshop of the renowned English artist Stanley William Hayter, whom she would later marry. A hub of avant-garde experimentation, the atelier transcended generational and stylistic divisions, serving artists who subsequently came to be seen as belonging to separate movements. Among its attendees were Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró, André Masson, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Gabor Peterdi, and Nina Negri, to name a few.

Stimulated by the literary Surrealist movement and an interest in pure form, Phillips abandoned her stylized and formalized technique for a more personal style, which she called “ambiguous poetic image.” Her new style combined abstract content with the ambiguity of Surrealist concepts: a mixture of people, plants, and animal forms derived from nature, inviting the onlooker’s interpretation.

As the political situation worsened in Europe and another war seemed imminent, Phillips and Hayter, who had been openly living together since 1937, left together for London when he was called on to serve his country in 1939. Due to Hayter’s political stance and commitment (he had produced two portfolios in aid of the Spanish Republic), there was some urgency for the couple to flee France before German forces invaded. Both artists were forced to abandon most of their works in Paris. Later, collector and dealer Peggy Guggenheim was able to retrieve some of their work (including Hayter’s important painting Parturition, 1939), but most works were lost and, so far, never recovered.

The couple began working with Roland Penrose, Ernö Goldfinger, and Julian Trevelyan in the Industrial Camouflage Research Unit, where artists helped civilian businesses use camouflage to defend against air raids. During these nerve-racking months, Phillips kept sculpting any way she could, and she also made prints at Julian Trevelyan’s studio at Durham Wharf. Apart from Trevelyan, Hayter and Phillips’s close circle of friends included John Buckland-Wright, Anthony Gross, Lee Miller, and Roland Penrose. Phillips also became close to Ërno and Ursula Goldfinger during this time. She and Hayter decided to leave Europe for the United States in 1940.

Due to immigration issues, Hayter left in an Allied convoy from Liverpool, landing at a Canadian port and then boarding a train bound for New York, while Phillips, then pregnant with their first son, left on one of the last American refugee boats bound for New York. They stayed for a week with Gordon Onslow Ford before leaving for San Francisco, where Hayter had a summer teaching position lined up at the California School of Fine Arts. On their way to California, Phillips and Hayter were married in Reno, Nevada. Their first child was born at the end of August, seven weeks prematurely. Once the summer session was over, Hayter returned to New York, where he had been invited to teach and reestablish Atelier 17 at the New School for Social Research. Phillips arrived in New York with their infant son at the beginning of December, and they moved into a two-bedroom apartment on 14th Steet and Seventh Avenue. It was spacious, but it still did not have enough room for them to work.

Within just a few years of arriving in New York, Phillips made a name for herself. Besides being published in the prestigious avant-garde art magazine Tiger’s Eye, her work was included in many significant exhibitions. In 1941, her hieratic sculpture Inverted Head (1941) was included in Surrealism, an exhibition organized by Roberto Matta at the New School for Social Research. In 1945, she displayed her carved limestone sculpture Genetrix (1943) in the second Women exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery (the first was called 31 Women, 1943). In 1947 she was represented by her sculptures Moto Perpetuo (1944–45) and Dualism (1944–45) in the landmark exhibition Bloodflames, curated by Nicholas Calas, at New York’s Hugo Gallery. Included in this important exhibition were some of the most significant representatives of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism: Isamu Noguchi, Roberto Matta, David Hare, Wilfredo Lam, Arshile Gorky, and Jeanne Reynal.

In 1944 Phillips and Hayter moved into a brownstone on Waverly Place, which finally afforded them the space for their professional, social, and family needs. Here Phillips settled her sculpture studio in the old dining room at the front of the building and began to cut stone again in the backyard, while Hayter used an upstairs room for his painting and drawing. The large kitchen became a frequent gathering place for their friends—among them Marc Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz, André Masson, and Joan Miró—to exchange ideas about art.

Phillips and Hayter were featured in Sidney Janis’s 1949 exhibition Artists: Man and Wife, which paired artist couples: Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp. Clement Greenberg’s assessment of the show offered qualified praise for Phillips at the expense of the other women artists represented: he wrote “Helen Phillips was the only woman whose work equaled that of the man.” This backward compliment reflects a broader critical perception that women artists were in a subordinate position to men during that era. But Phillips’s reputation had grown to the point of being asked to join the male-dominated Eighth Street Club, whose members included Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, Isamu Noguchi, and David Hare, among others.

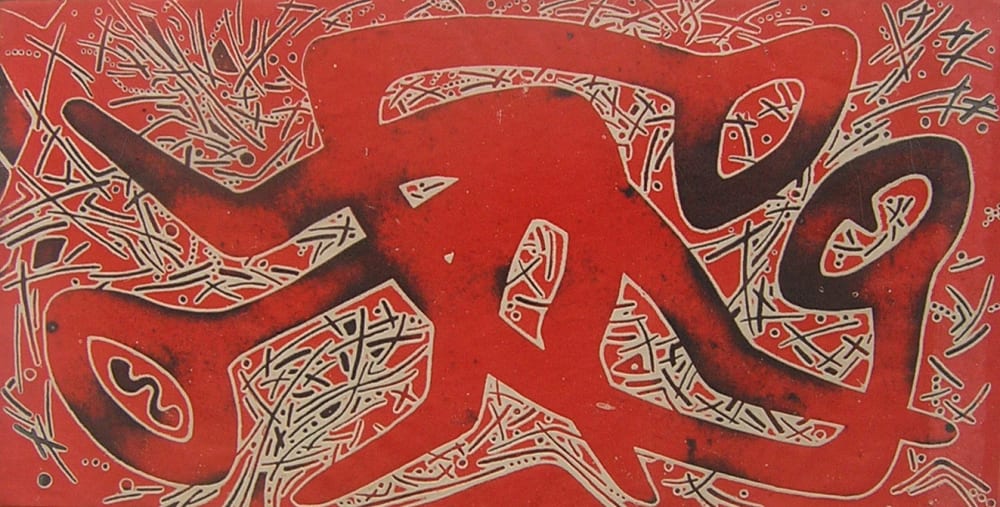

After Hayter and Phillips’s return to France in the early summer of 1950, Phillips was invited by André Chanson, director of the Petit Palais, to showcase fourteen sculptures in the exhibition New-York: Six Sculptures de Doris Caesar, Klys Caparn, Minna Harkary, Helen Phillips, Helena Simkhovitch, Arline Wingate, and thereafter was invited to exhibit in numerous European international biennials and salons. In the late fall of 1950, Hayter reopened Atelier 17, and over the next four years, having become bored with black-and-white engraving, Phillips developed her own method of making color prints, using deep bite and simultaneous color printing.

In the 1950s the French poet André Lothe, in the Parisian newspaper Combat, called for artists and intellectuals to settle in the houses and ruins of Alba-la-Romaine, an idyllic, medieval town in the Ardèche region of southern France. Lothe’s article made the rounds in the cafés of Montparnasse, and many artists of the Paris School decided to leave the postwar struggles of the city for the charm and serenity of Alba. Artists of all nationalities purchased and settled in about thirty houses there, establishing an international art scene in an otherwise quiet, provincial town. Phillips and Hayter were among those who joined this artists’ community: in 1953 the couple purchased an old stone house where they had adjoining studios. They would go on to spend most of their summers in Alba with their children, finding fulfillment and inspiration in nature and a simpler way of life.

In Alba, Phillips began carving 300–400-year-old oak trees found nearby and created multiple large-scale totems, one titled Family Totem (1953), reaching a height of seventeen feet. She continued to work in her “ambiguous poetic image” style, which was strongly influenced by her interest in ethnographic arts, merging human forms with the natural world. A pair of totem-like figures titled Eve (1958) and Adam (1960) were purchased by the Dallas Museum of Art in 1960.

In 1956, at Ërno Goldfinger’s invitation, Phillips participated in the breakthrough exhibition This Is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, with a hanging sculpture carved from balsa wood titled Suspended Figure (1956). The original piece, purchased by Goldfinger, is now lost, but a cast in aluminum survives in the Goldfinger residence, with striking photographic documentation of the artist posing next to the original. From the 1950s on, Phillips made sculptures using a range of techniques and materials, including bronze (which she would cast and then polish), wood, stone, plaster, and other metals.

Many of Phillips’s sculptures from this time were exhibited in Paris at the Musée Rodin, Salon de Maie, Galerie Pierre, Galerie La Hune, and consistently throughout Europe, where she was often called on to represent the United States. In the United States she was included as part of a 1962 traveling exhibition, 14 Americans in France, which was initiated by and on view at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, DC, and traveled elsewhere in the country.

In 1967, Phillips severely injured her back while transporting her large stone sculpture, Alabaster Column (1966), which the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York (now the Buffalo AKG Art Museum), had recently purchased and currently lists in its collection as Forme abstraite (Abstract form), (1967). Her injury greatly affected her ability to sculpt for almost a decade, yet she continued to create. Once recovered, Phillips returned to sculpting and printmaking with the same drive and dedication as before, but on a more intimate and manageable scale. Continuing her explorations in modular growth, geometric unity, and the “universal model,” Phillips created a significant late body of work far removed from her earlier styles. She replaced her “ambiguous poetic image” with well-defined geometric structures: she used lightweight wire like an inky pen to draw through space, creating new forms that relate more to science, technology, and the space age than to ancient, precolonial, or Surreal imagery. These new structures pay homage to her lifelong friendship with Alexander Calder and deep admiration for Buckminster Fuller, two visionaries who enormously impacted the twentieth century.

Her graphic works always reflected what was going on in her sculptures. When the physically demanding technique of engraving into copper or zinc became too challenging, she pivoted to creating relief prints in linoleum. She took great care carving repetitive linear patterns in an abstract and minimal style, reflecting her interest in wave theory, refracted light, and the Fibonacci sequence (golden ratio). Her prints from the 1970s and 1980s embrace color theory and the effects of light as their main subjects. She continued to explore new ways of creating until her death in 1995.