-

“Artists are an important part of the community. By their very presence, they make a statement.”

Robert Blackburn -

-

Blackburn received his initial formal art instruction while attending PS 139, Frederick Douglass Junior High School, in Harlem. These formative years coincided with the advent of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1935, a program initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt that aimed to alleviate unemployment while preserving professional skills and fostering self-respect among American workers. Notable artists such as Ilya Bolotowsky, Norman Lewis, Sollace J. Glenn, Zell Ingram, and Ted Witonski were involved in the WPA project at PS 139. Additionally, Harlem Renaissance luminaries Countee Cullen and William Artis were part of the school's staff, with Blackburn assuming the role of art editor for Pilot magazine. In recognition of his talents, he was awarded the Frederick Douglas Guidance and Art Medals in 1936.

-

-

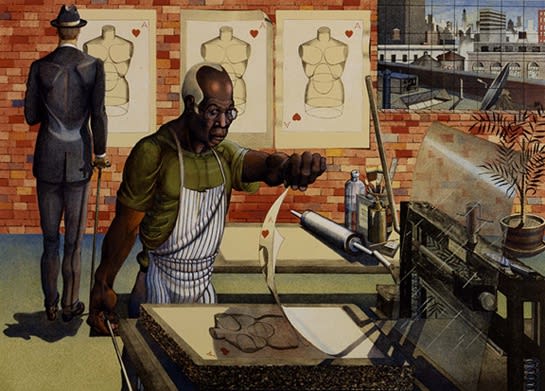

Blackburn's initiation into lithography at Dewitt Clinton High School shows an awareness of Social Realism and Regionalist painting in his early works, earning him accolades in national art competitions. In 1939, he was awarded both a St. Gaudens Medal for excellence in art and an Art Students League Working Scholarship, enabling him to study at the Art Students League of New York (ASL). Upon enrolling at ASL, he shared living quarters with Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Ronald Joseph, and writers William Attaway and Claude McKay. Blackburn pursued classes with Vaclav Vytlacil at ASL, drawn by Vytlacil's philosophical and aesthetic approach. He subsequently apprenticed under Will Barnet, absorbing Barnet's holistic view of printmaking as a fine art form comparable to painting and sculpture. After studying at the Harrison School of Art and gaining awareness among friends at Stanley William Hayter's Atelier 17, Blackburn was further fortified in his resolve to establish his own printing workshop. He envisioned a space where artists of diverse backgrounds could collaborate and explore the creative potential of printmaking.

-

In October 1947, Blackburn acquired his first litho press and a spacious loft located at 111 W 17th Street, where he lived with Harry Hoehn and three other artists. Hoehn and Blackburn were acquainted from high school, and Hoehn also participated in classes at the Arts Students League and Atelier 17. This new studio proved highly conducive to sustained creative work. Often, they would print day and night, organically fostering an atmosphere where each artist enjoyed the freedom to create in their own manner and at their own pace, nurturing their unique creative processes. Unbeknownst to them, the Print Making Workshop had begun. In Blackburn's words, “. . . there was no possibility to teach. So I said, well, I’ll just start my own little thing and print for other artists. Then the idea came to have other people do their work because I had friends who came over who wanted to work on their own . . . Printing was something that I like to do, I mean, I like the idea of making the prints for myself, and liked lithography, and I thought it was an important thing both socially because I had a very social—I now know it, there it is, it’s my cause.”

-

-

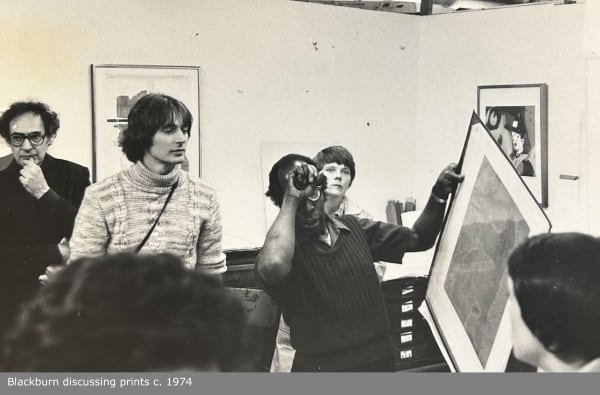

"The Printmaking Workshop, under the direction of Robert Blackburn since 1948, offers studio space and printmaking facilities for etching, lithography, relief, and photography. Here artists share a common creative interest, working together for the purpose of producing and exhibiting fine print works. The Workshop comprises six thousand square feet of floor space that includes dedicated areas for open workshops, evening classes, private editioning, and photographic work."

Maudra Jones, The International Review of African American Art (IRAAA), Vol. 6, No. 4 (1984)

-

Blackburn's apprenticeship under Barnet went far beyond mere study. He also served as Barnet's assistant, which afforded him deep insights into Barnet's artistic principles and his technical expertise. Together, they swiftly delved into the unexplored potential of their chosen medium. As time passed, their relationship matured from a traditional mentor-student dynamic into a partnership between equals driven by a shared passion for pushing the boundaries of lithography.

"We wanted the stone, and what we did on the stone to express the same ideals of painting only they were graphic in nature. They had a different look to them, they had to deal with paper instead of canvas . . . we used the stone in a very free way," Barnet remembers. Through experimentation with washes and layering, they achieved a depth of texture with diverse grounds. They dug into the stone, approaching it like a mutton to create pattern that would hold in both physically and chemically. The stone, once a passive surface, became an active medium in itself. Barnet found in Blackburn a kindred spirit, both unafraid to blur the lines between printmaking and painting, regarding the matrix not merely as a surface but as a three-dimensional form. Together, they challenged the conventional practices of lithography.

At the time, it was rare for artists to handle the printing presses themselves; typically, artists would draw on stones, which would then be entrusted to professional printers for editioning. Across much of the Western world, printers guarded their craft's secrets closely, a tradition upheld even at the Art Students League. However, Blackburn and Barnet were both artists and printers.

On the weekends, Blackburn would assist Barnet in printing the accomplished work of students and prominent artists alike. It was through such work with Barnet that Blackburn gained the basis of his technical knowledge.

-

"It was not long after the Creative Graphic Workshop was established that it attracted the attention and financial support of Will Barnet, Blackburn's "friend, teacher, advisor, and mentor." Barnet's support was soon joined by that of John Van Wicht, Margot Steigman Robinson, Priscilla Haley, and Dan Suerdloff, among the many who "shared in the struggle and the belief that such a workshop was important to serve the creative needs of artists regardless of their esthetic, political, social, economic, or racial persuasion."

Samella Lewis and Bob Biddle,The International Review of African American Art (IRAAA),Vol. 6, No. 4 (1984) -

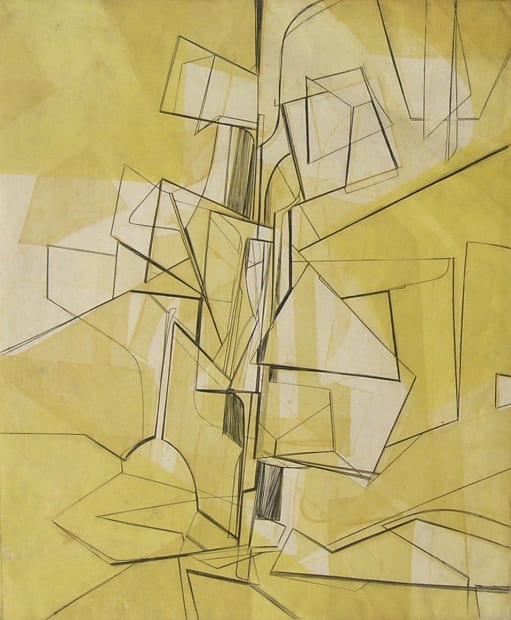

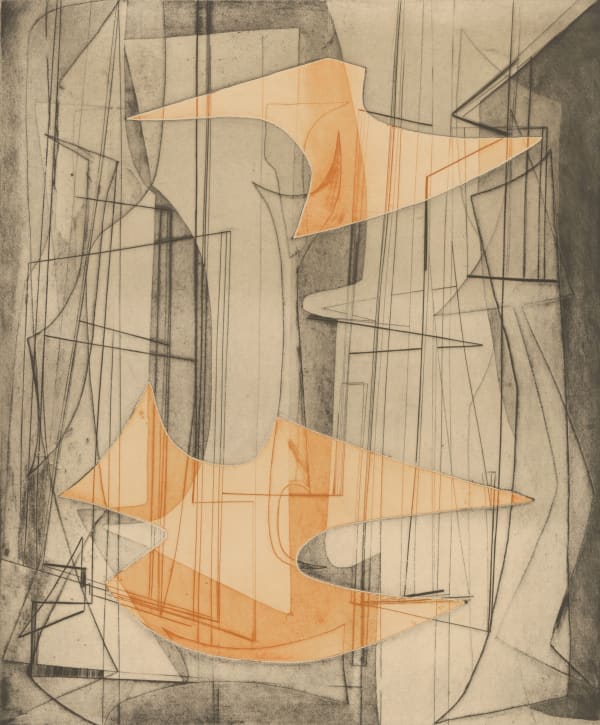

Between 1951 and 1952, Barnet came to work at Blackburn’s studio, where they produced a groundbreaking series of experimental color lithographs using more than a dozen stones in the creation of one image—a feat virtually unheard of at that time. Blackburn wrote, “I often worked with him (Barnet), employing as many as 17 stones in one print and using techniques unfamiliar to American printmaking. These pre-date all printmaking of recent years and should hold a special place in its history."

In 1953, Blackburn won a John Hay Whitney Travel Fellowship for travel and study in Paris. He sought out the famed lithography studio Desjobert. He was soon disappointed, as the nature of works made at Desjobert separated the artist from the printer. Instead, he studied with seminal cubist painter André L’Hote for six months, talking intensely about abstract art. Blackburn enjoyed the city. Terry Haass arranged a room in a hotel for him, and he reconnected with Americans Ed Clark and Beauford Delaney. He met Krishna Reddy and printer Roger Lecourière. Riva Helfond visited near the end of Blackburn’s stay, and as Riva previously knew Delaney, they all spent time together. Blackburn and Helfond traveled around the French countryside on a motorbike.

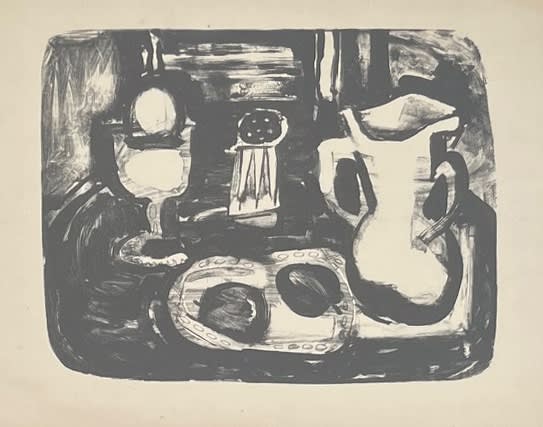

This year abroad left a great impression on Blackburn, who already drew much inspiration from European Modernism in his own work. Spending a significant amount of time connecting with European artists, visiting museums, working in traditional and avante-garde studios and printshops, traveling the countryside, and experiencing different cultures rejuvenated his soul. We can witness the fruits of his inspiration in a series of abstracted still-life lithographs created upon his return.

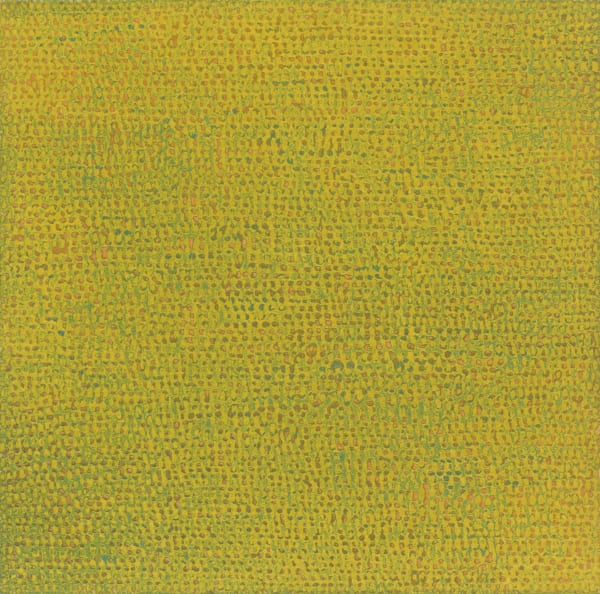

By 1955, he was back at his own press producing lithographs, primarily still lives but eventually abstractions, where he worked through variations of color, compositional rotations, and colors.

-

Atelier 17, founded by the innovative printmaker Stanley William Hayter in Paris in 1927, relocated to New York City due to the outbreak of World War II. By 1948, it had moved from the New School for Social Research to 41 East 8th Street near Washington Square Park, just a 20-minute walk to Robert Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop. Atelier 17 attracted a diverse array of artists who were drawn to its environment of exploration and its commitment to pushing the boundaries of traditional printmaking methods. Through its workshops and exhibitions, Atelier 17 played a pivotal role in shaping the development of modern printmaking in America.Blackburn later recalled, "At that time, there were no workshops, either professional or otherwise, in New York. . . . There were only regular art schools, such as the Art Students League, Pratt Institute, and small print departments at NYU Art Education, Columbia Teachers' College, Hunter College, and the Brooklyn Museum Art School. These were all primarily adequate for art teachers and a few painters and sculptors." In Blackburn's view, the need for a place where professional printmakers could work and where emerging artists of all ages could study at evening classes was indeed apparent. Under his direction until 1952, the Creative Graphic Workshop served as an independent, alternative space for art students and developing artists.Although it goes unmentioned in the above quote, Blackburn was well aware of Atelier 17. He and Hayter held each other in the highest regard and remained friends throughout their lives. The overarching philosophy for each of their workshops embodied a commitment to artistic innovation, technical excellence, and a spirit of artistic camaraderie that transcended societal and economic boundaries. Each studio laid the groundwork for both a more inclusive and experimental approach to printmaking and art making as a whole. Each studio drew artists from all over the world as word of each distinct opportunity spread. Indeed, printmaking continues to be guided by the pedagogical methods of Hayter and Blackburn.

-

“My first love was lithography, the most complex of the printing mediums. But my second love is etching.”

Robert Blackburn -

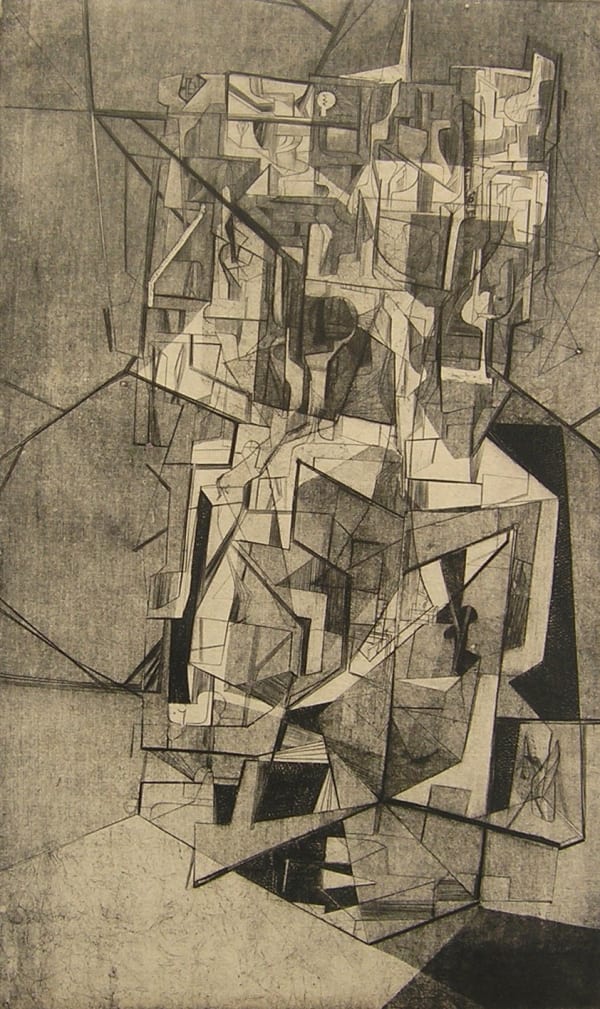

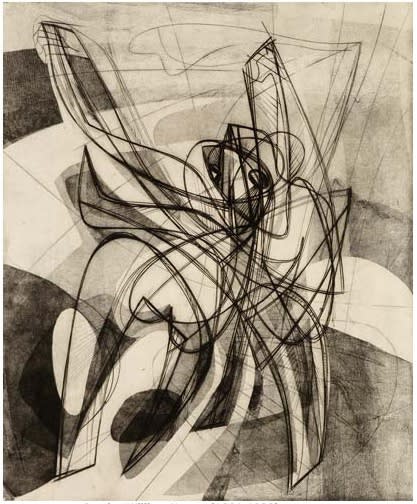

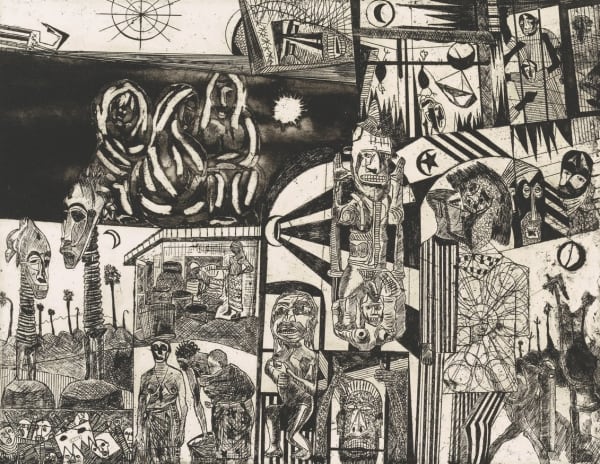

We are proud to include a group of 3 working proofs that we believe were made in the 1950s. The three state proofs record the development of Blackburn’s ideas. The first sheet has the basic composition mapped out and serves as an armature upon which Blackburn explored options for further additions; the second sheet reveals the results of additional etched passages, along with further drawing upon the proof with ink wash; and the third sheet includes further steps in the process with more commitment via etched shapes and graphite drawing, where careful, highly intentional cross-hatched lines indicate further thinking upon this third trial proof.

We have yet to discover a final proof, and it may be true that these proofs are as far as Blackburn went with this particular plate. Demonstrating the nature of his approach to making an etching, and the care and craftsmanship of his mark-making serve as evidence of his decision-making within the process allowing us to know more about what was important to Blackburn. The set of working proofs also serves as a testament to the pedagogical nature inherent in printmaking.

-

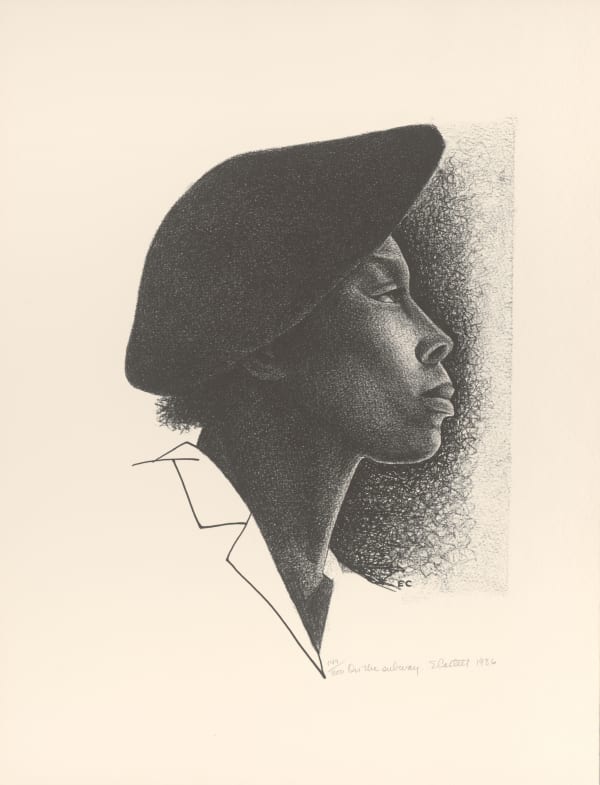

Born Terezie Goldmannová in 1923 in Český Těšín, then part of Czechoslovakia, Terry Haass was raised in a region dominated by Germanic influences. Fleeing the rise of antisemitism and German aggression in 1938, her family sought refuge in Paris, where Terry immersed herself in fashion and art courses at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. As war engulfed Europe, they were smuggled through Andorra to Portugal, eventually securing passage to New York in April 1941. Upon her arrival, Terry promptly enrolled in printmaking classes at the Arts Students League under the guidance of Will Barnet, where she forged a lasting friendship with her talented classmate, Robert Blackburn.

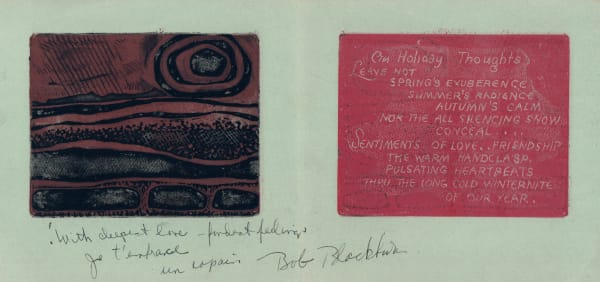

During the early 1950s, Terry deepened her acquaintance with Blackburn while serving as the workshop manager at Atelier 17. Their bond endured throughout their lives, with Blackburn becoming an integral part of Terry’s family circle, enjoying home-cooked meals and stimulating conversations with her mother. The holiday card preserved in Terry’s collection, sent by Bob Blackburn, is witness to their enduring connection.

-

In 1947, Terry Haass embarked on her journey with Atelier 17, then situated at 41 East 8th Street, above Rosenthal's artist's supplies store. Here, she was introduced to the intricacies of burin engraving, its processes, and its materials, which paved the way for her exploration of abstraction. Over her illustrious 60+ year career, Haass’s artistic evolution mirrored her profound reverence for physics, the natural world, and her immediate surroundings. From her early lithographs depicting the social realities of wartime to the uninhibited exploration fostered at Hayter's Atelier 17 and onwards to her abstract expressionist etchings that evoke terrestrial formations and atmospheric phenomena, Haass’s oeuvre encapsulates a ceaseless quest for transformation and intellectual curiosity.

-

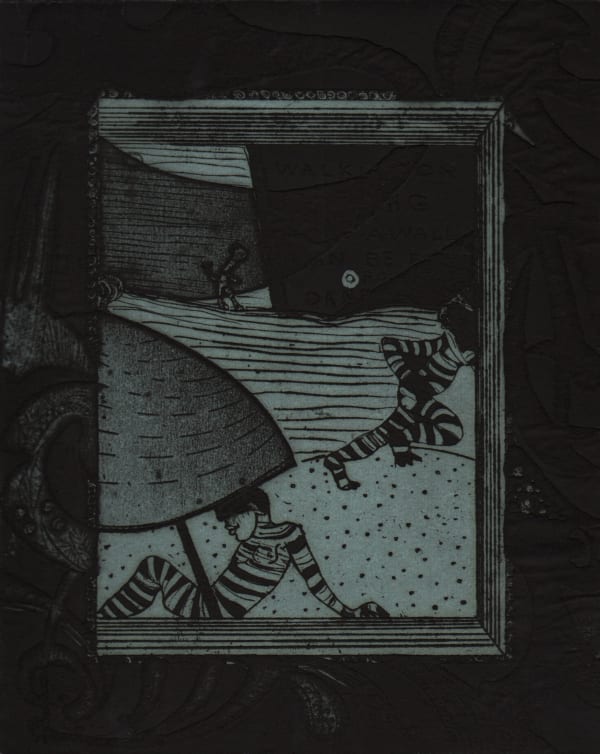

One of the constant threads through our exhibition is viscosity printing, also known as simultaneous color printing. The technique was developed in 1952 at Atelier 17, and Hayter is often credited for it. However, Krishna Reddy (born 1925, in Andhra Pradesh, India) and Arun Bose (born 1934, in Dacca [now Dhaka], then part of British India [now Bangladesh]) were among the very first, along with Hayter, to experiment with simultaneous color printing. They discovered the process when an inked brayer or roller was inadvertently rolled over some clear oil. They noticed that the oil acted as a resist to the ink. They rolled the oil/ink onto a plate and printed the accident. Thus, a new way of printing color was born. They then developed the idea further by rolling color over color and varying the amounts of oil in the inks, enabling the artists to print colors simultaneously on a single plate. The resulting prints had a depth of color and expression previously unknown.

-

Krishna Reddy and Blackburn first met in Paris in 1953 and became friends. They met again while Krishna was visiting in 1964, and on the occasion of his second visit in 1968, Blackburn invited Reddy to teach a workshop at his studio.

Many artists at Atelier 17 and Blackburn's workshop embraced the viscosity method, and we are delighted to share superb examples. From the earliest examples, Reddy’s Insect 1952, Hayter’s About Boats, and Witches Sabbath changed how artists thought about etching, deeply etched (bitten) plates and applying color. This led to new kinds of expression. Reddy explored numerous color variations or color trial proofs from a single plate before deciding on final state and solution for creating an edition. He did a great deal of research into the physical properties of printing inks and how to manipulate them. This approach dovetailed with Hayter's background in the chemical properties of oil and dating to his work in the oil fields of then Persia in the 1920s. Adding oil or magnesium sulfate served the purpose of making the inks better behaved for the sake of consistency and allowing artists to apply layers of colors onto a single plate. A single plate and a single run through the press produced the highly satisfying depth of color evident in the examples shared here. The density of rollers to apply layers of inks to plates is another aspect of simultaneous printing, addressing the desire to have some inks sit on the surface of the plate while other colors are applied to the recessed, etched hollows in a plate.He and Helen Phillips brought a sculptor’s point of view to the process, treating various depths of etched surface as shallow relief and exploiting color possibilities. “I approached printmaking as a sculptor and brought about significant changes both in plate preparation and color printing…maximum simplicity and directness while increasing the expressiveness and the intensity of my images” was Krishna’s goal. Bob Blackburn wrote, “His (Reddy’s) comprehension of the metal plate as sculpture below the surface, broken up into myriad cavities that retain colour in various densities gives a luminous, rich multicolored image.” And, “America was fortunate that Krishna had continued in the tradition of the Atelier (17).”

This new way of using color coincided with the moment when abstract expressionism became the leading edge of international art. Viscosity, or simultaneous color printing, became a ubiquitous technique at Blackburn's workshop and, as evidenced here, many artists made the technique their own.

-

"A mixture of intaglio, relief, and the operations of chance, this technique appeals to those artists who would emphasize uniqueness in their graphics. The technique is credited to Krishna Reddy while at Stanley William Hayter's workshop. A zinc plate is etched or engraved to roughly two different levels, and its relief surface is either textured or left plain. Then three inks of differing tackinesses (three viscosities) are applied: the thickest to the deeper recesses,the thinnest to the upper level of the intaglio, and the ink of middle viscosity to the highest, the relief surface of the plate. These inks are usually of three different colors and, since their viscosities differ, they interact somewhat unpredictably. Since the inks are applied by hand, there is another element of chance present-another reason why no two prints come off the same plate alike. The print is pulled from a single pass through the press. It is easy to see Hayter's influence in this technique, for it is suited to producing work of abstract form and color. It also challenges the boundaries of printmaking: in this age where commercial printing presses can turn out ten million identical copies, the artist is asking whether it is appropriate to ape that kind of duplication. As a consequence, printmaking - or, rather, a vanguard of printmakers is withdrawing from graphics' traditional role of supplying expressive art for many, and is valuing uniqueness the way painters and sculptors have. We suspect that when this period of consolidation is over there will indeed be an invigorated interest in uniqueness, but there will continue to be multiple copies of predictable similarity and with a delicacy of expression that commercial printing cannot achieve: for that is the essence of printmaking, that strength which has given graphics the ability to endure and adapt for as long as it has." — Samella Lewis and Bob Biddle, The International Review of African American Art (IRAAA), Vol. 6, No. 4 (1984)

-

Kathy Caraccio enrolled at the newly created Herbert H. Lehman College in the late 1960s, and her first printmaking instructor was engraver Richard Ziemann. When Ziemann left for a sabbatical and Arun Bose took his place. Bose had just arrived from Paris, where he’d worked with Hayter at Atelier 17, and arrived with a newly acquired printing technique called color viscosity. Arun Bose also worked as a master printer at Blackburn’s PMW.

“Arun’s first class was a viscosity printing lesson which utilized color ink, rollers to apply the inks to the metal plates, and oil. I realized right then that I could draw, paint and print all in one class.” Bose loved teaching, playing with color, and inventing new unconventional printing approaches. "Arun was a father figure, a mentor, and someone who set the example of practicing art making enthusiastically. Most of all, he treated me like an artist not a student. I wanted to use the presses as an alumni and the art office said I could if my teacher gave me permission. So I went to Arun and he said, “no, you don’t want to do that, you want to go to Blackburns.”

-

“Bob had an open door, shirt off his back policy. He invited everybody in. If you couldn’t pay, you didn’t have to. He would just say 'get to work.' Being in Manhattan, he attracted many international students and artists who fell in love with the potential of printmaking.”

"It was a profound opportunity to think about the artists working at PMW and where they were located geographically and listen to artists share their culture and learn about the printmaking techniques. It was always interested to talk to international artists because many other cultures have a much longer tradition of printmaking." — excerpted from Kathy Caraccio, Right Place, Right Time: The Rest Is History — Becoming a Master Printer and Collector with Bob Blackburn (New York, 2021)

-

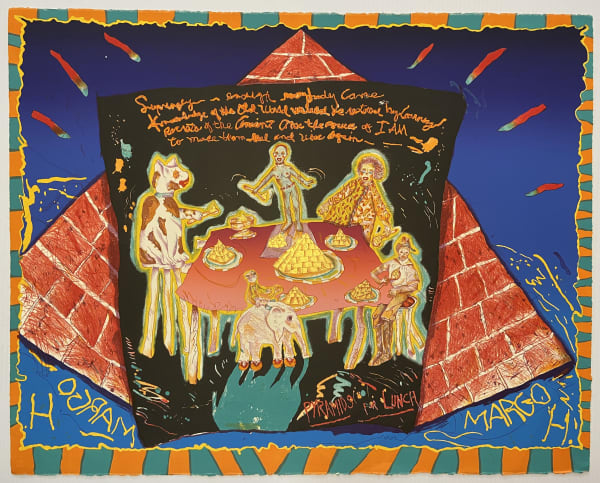

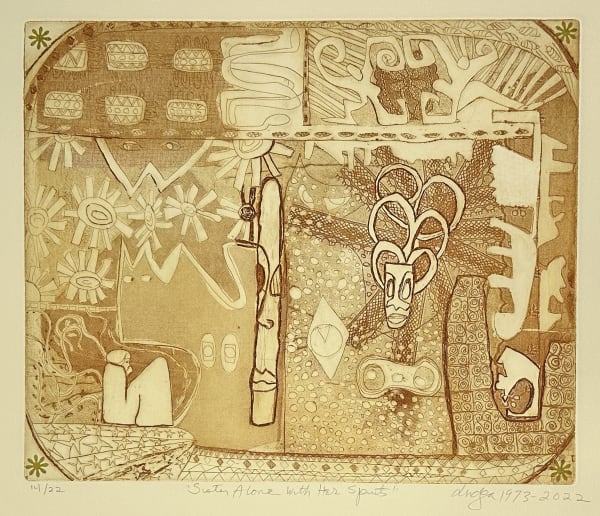

"Using the synergy inherent in abstraction, I populate my work with seemingly random numbers, marks, words, and symbols, letters, multiple degrees of vibrant, cool/hot color, and the narrative imagery of storytelling. I want my art to encourage broad, diverse audiences to explore, conjecture, wonder, recall memories, and experience ways that visual imagery can connect us to our spiritual yet universal selves. Using abstract geometry as a compositional structure, and the sacred in art as a “content guide,” I create the magic of a poetic, meaningful, and moving art."

Joyce Wellman -

Joyce Wellman is an accomplished artist who engages in persistent experimentation with ideas, media, composition, and materials. The body of her abstract art references the subconscious mind and explores the language of dreams. Blending the genres of painting, drawing, and printmaking, she has pushed her ideas and concepts to generate new pathways of exploration. Her work invites the viewer into an enigmatic conversation with the unconscious.

At the Studio Museum, Wellman studied with printmaker Valerie Maynard. Searching for "anything that was free," she also attended the Public Theater's photography workshop and Blackburn's Printmaking Workshop of New York City, which provide evening classes where emerging artists of all ages can learn the techniques of established professionals.

Wellman's early prints were shown at the Cinque, a gallery originating from the generous concerns of its founders, Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, and Ernest Crichlow. One of its purposes was to provide exposure for young African American artists. Gallery director Chris Shelton "was very open, welcoming, giving," Wellman recalls. "I educated myself there. I was very shy, hoping that I could have a show there one day. Chris helped make that dream come true. We hung out. I met other artists. And I felt very lucky - "there were no gender issues (e.g., sexual harassment)."

Another early mentor was Ed Clark. Helping Clark stretch and frame his 25-foot-high canvasses, Wellman was inspired to explore her potential as a painter. Her development as a printmaker continued at the Color Print Atelier under the tutelage of Krishna Reddy, the "father", according to Wellman, of color viscosity printing." —Richard Powell, The International Review of African American Art (IRAAA), Vol. 10, No. 3 (1993)

-

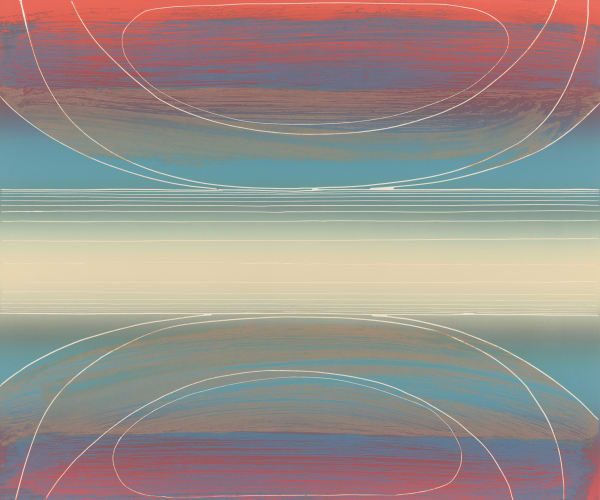

In Montparnasse, Paris, under a fourth-floor studio skylight, Clark developed his signature push-broom technique. Dissatisfied with the wavering gestures of a hand brush, he used the broom to extend his reach and rush long, energetic strokes of paint horizontally across his canvases. Color is mixed luminously and directly on the painting’s surface. This innovation, coupled with the oval-shaped canvases of his later years – which Clark felt better matched the human field of vision – allowed Clark to achieve what art historian Darby English notes as a unique “dimensionality of color” that does away with “head-on representations of the world.”

Over a period of 25 years, Clark worked with the famed studio of Robert Blackburn to produce a number of intaglio and relief prints. We are pleased to present a selection of these works, dating from 1976 to 1997. Combining luscious color blends, etched horizontal lines, and the ellipse as a central motif, these works offer a rich, potent and yet understudied account of how Blackburn's masterful knowledge of printmaking offered Clark a means to distill many of his paintings' key elements into discrete printerly moves. -

Compared to traditional printmaking techniques like etching, engraving, and relief printing, lithography stands out for its planographic nature. Unlike the intaglio methods of etching and engraving, where incised lines hold ink, or the relief printing process, where the ink is applied to raised surfaces, lithography relies on the smooth surface of the stone or plate. This characteristic makes lithography well-suited for capturing intricate details and achieving a wider range of tonal values. Its versatility allows artists to experiment with various drawing and painting techniques directly on the printing surface, providing a unique space for creative expression.

"During the mid-1950s Robert Blackburn's printmaking workshop was run by a loose cooperative of artist-friends while he spent a year and a half in Paris and Europe under the auspices of a prestigious John Hay Whitney Traveling Fellowship. After his return to New York, he was hired in 1957 as the first master printer at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), the lithographic venture founded by Tatyana and Maurice Grosman, based in West Islip, Long Island. At ULAE, he printed for an emerging generation of artists including, Larry Rivers, Grace Hartigan, Helen Frankenthaler, and Robert Rauschenberg. His predilections and fluency with the medium contributed to the new “look” of these works, which would define the American “graphics boom.”

During this active period, Blackburn's color graphics reached a creative and technical zenith. In 1963, he began to operate his own Manhattan workshop full time, providing an open graphics studio for artists of diverse social and economic backgrounds, ethnicities, styles, and levels of expertise. Under his direction, the Printmaking Workshop became one of the most vital collaborative art studios in the world.

Robert Blackburn's commitment to nurturing artistic talent and his advocacy for printmaking as a legitimate form of artistic expression contributed to the broader recognition and appreciation of lithography within the American art community." — Creative Space: Fifty Years of Robert Blackburn's Printmaking Workshop, A Graphics Explosion (Library of Congress exhibition, 2003)

-

-

Ronald Joseph and Blackburn studied lithography in the 1930s at Harlem Community Arts Center under Riva Helfond. Tom Laidman met Blackburn a few years later while studying with Will Barnet at the Arts Students League (ASL). Both men would stay close to Blackburn throughout their lives, continuing to advance each other's art practice through camaraderie and good-natured competition. Blackburn credits Joseph for helping him remain focused on his own work. They made sketches or "notations" together in various parks in the greater New York Metropolitan area. Joseph won a Rosenwald Fellowship in 1948, taking him to Peru and then Paris, where he studied at the Grande Chaumière. In 1956, he left for Brussels, returning in 1989 to renew friendships, including the opportunity to make lithographs with Blackburn, including Untitled c . 1990, with its expertly printed rich black tones.

Tom Laidman became a close friend of Blackburn at ASL and was an early participant in his workshop: “When I came there in 1950, the Shop was on West 17th Street in a four-story red brick building,” Laidman recalled. “There was no elevator, and everything in the place went up on our backs, including the presses, stones, lumber for building, coal for the stove in the middle of the shop. We froze in the winter, roasted in the heat in summer, and the heat didn’t make the printing any easier. We went through all kinds of maneuvers to keep the images in the stones from filling in. The atmosphere was friendly and intimate,” Laidman said. “There was an open arrangement where … students and artists had unlimited access. There were three or four litho presses, and we’d all fight for press time. Bob was a dynamo of energy.”

-

Blackburn's establishment of the Printmaking Workshop in New York City in 1948 signified a pivotal moment in the evolution of African American artistic discourse. It served not only as a space for artistic refinement but also as a hub for cultural production and dissemination, fostering exploration of identity, tradition, and innovation within a socio-political context. Benjamin Wigfall later replicated this model with Communications Village in Kingston, NY in 1973.

Hailing from Churchville, Virginia, where he first found solace in the arts, Wigfall's journey included teaching at Hampton Institute (1955-1963) before becoming SUNY New Paltz's first Black art professor. His Communications Village became a vibrant community-focused print shop offering diverse classes and lectures, sparking discussions on social and cultural influences. Through visiting artist programs, Wigfall connected artists and locals, fostering a sense of shared identity and purpose.

Wigfall's story emphasizes the transformative power of artistic collaboration in socio-cultural emancipation, echoing Blackburn's impact. Their workshops remain symbols of African American artistry's enduring legacy, challenging and reimagining the world we inhabit.

-

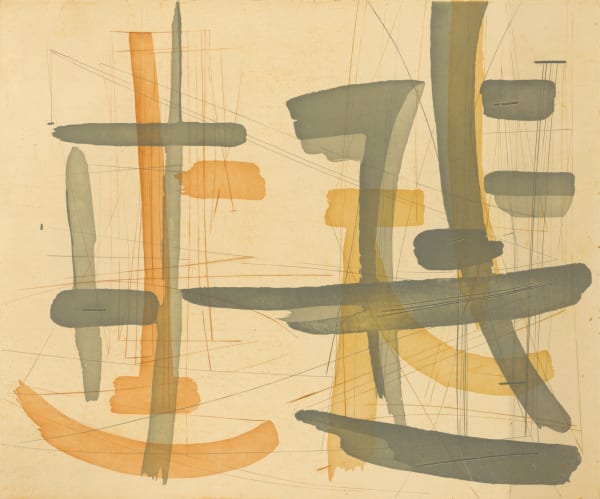

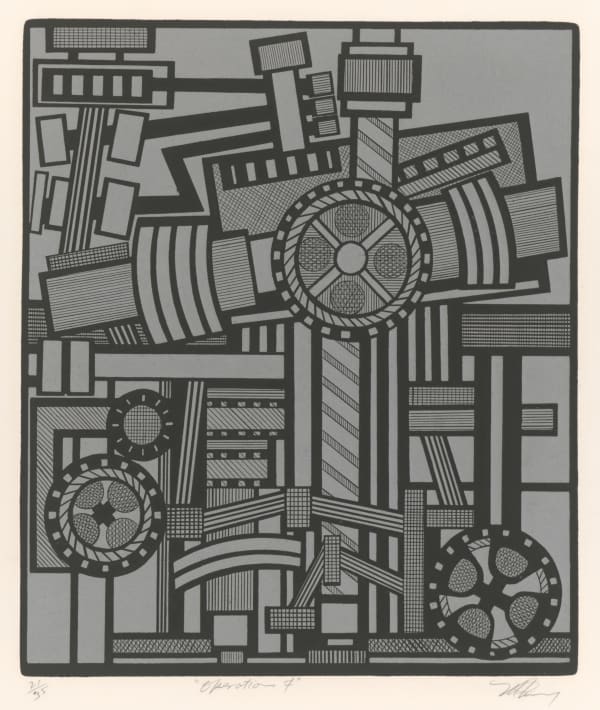

Revisiting matrices was a method frequently employed by Blackburn to stimulate new creations throughout his career. Beyond merely experimenting with alternate color proofs, he consistently manipulated his compositions, seamlessly transitioning between vertical and horizontal formats and embracing the endless array of variations they offered. This can be seen when comparing Jay Talk Hawk 1975 and Miss Unity 1990, where the same woodblocks are utilized in different orientations.

Additionally, Untitled, 2000 represents another instance where Blackburn revisited and reinvented his earlier work Sunlight and Shadows 1960s-70s. In the later printing, he stripped the compostion down to its most essential.

Organic Things 2001 was first printed in the 1979 under the title Forms and Experiment, but was reprinted 30 years after with multiple variations using the simultaneous color viscosity technique.

-

"Symbolizing the sum and substance of intercultural exchange and intergenerational communication, the Printmaking Workshop (PMW) of New York City provides a creative environment that involves all manner of artists and technicians in the sensitive, intimate collaboration of ideas, approaches, relationships, and techniques-"sharing a common, creative interest , .. working together for the purpose of producing and exhibiting fine print works." In essence, the PMW is engaged in executing the sixteenth-century concept of the artists' collective, for "the living of these days and for the generations to come. From its humble beginnings shortly after World War II, in the private workspace of Robert Blackburn, its founder and director, the PMW has evolved into a formidable institution serving a host of artists, researchers, and scholars, as well as its immediate community. In 1947, it was, in fact, the duality of purpose inherent in Blackburn's efforts-to practice his craft as a livelihood while serving as a printer for his fellow artists-that led to the creation of New York's first printmaking workshop, the Creative Graphic Studio."

Maudra Jones - IRAAA Vol. 6 Number 4 -

"Bob knew everyone, everywhere. The shop was a hive of activity. At any given moment, you could hear every type of music and a dozen languages from each corner of the loft. I never again met so many diverse and interesting people in one place at one time"

Deborah Cullen -

Blackburn welcomed in artists, friends, and friends of friends. The community grew, until it became an informal cooperative and then, in 1971, a nonprofit. As his influence spread, over the years the artists who came through his workshop would form their own communities, and Blackburn inspired new print shops in many places. In 1978 he traveled to Asilah in Morocco to found the Asilah print workshop there.

“It’s interesting to think how international modern art was in the 1970s,” curator Jonathan Canning said, marveling. “The idea of setting up an international print workshop in Morocco in the 1970s seems extraordinary.” (Kate Abbott - BTW Bershires, 2022)

-

"In 1974 Bob brought me a large, etched copper plate and proposed that I put some color on it. I ask who it was for, he said it didn’t matter that he would pay me for threes dates to proof with the viscosity set up I had. Bingo! That project ended up being for Romare Bearden’s images, The Train, and The Family. During the proofing stage with victory reliers I was free to explore —I had nobody telling me what they wanted."

"Bob was very smart to trust me to proceed with whatever instincts I had. He was a genius at implementing a printing project and tapping the resources of his membership. After a dozen proofs went to Romare and he added watercolor. Alex Rosenberg selected one to publish in his upcoming Bicentennial Portfolio. One came back to me to be editioned. I needed to add a watercolor plate, adjust some parts of the image and cut out many smaller sections for separate inking. The studio hired assistants to help me with the viscosity and the à la poupée color application." The Train became one of Romare Bearden’s most loved and coveted prints. — excerpted from Kathy Caraccio, Right Place, Right Time: The Rest Is History — Becoming a Master Printer and Collector with Bob Blackburn (New York, 2021)

-

In 1986, Maudra Jones wrote in The International Review of African American Art (IRAAA), "The years since 1947 have become documented history - a documented history of contemporary American graphics. Over three thousand fine prints, by more than five hundred artists, are contained in the Printmaking Workshop (PMW) collection, serving, in part, to document changes in techniques and concepts in printmaking.

Since receiving its first funding grant in 1970, the PMW's programs have received the support of such sponsors as the American Broadcasting Company, the Chase Manhattan Bank, the Chemical Bank, the Jerome Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Board of Education, the New York Department of Cultural Affairs, and the New York State Council on the Arts. Emma Amos, Benny Andrews, Betty Blayton, Vivian E. Browne, Eldzier Cortor, John Gerasimchik, Sergio Gonzalez-Tornero, Mohammad Khalil, Arlene Leder man, Norman Lewis, Shreedevi Munshi, Shiguri Nara kawa, Mike Nagano, A. J. Smith, and Carlos Suenos are among the many celebrated artists who have contributed their works to the PMW's collection.

In its expanded role, the PMW maintains an artists' workshop serving numerous young artists "as the locus of their individual maturation to full, realized artistic expression" and serving established artists "as a center of support, exchange, and as a professional base." The Workshop's ongoing efforts include a comprehensive community outreach program that serves a variety of constituencies (including the very young, the neglected, and the aged), continuous classes in etching, engraving, lithography, woodcut, and photo-mechanical processes, lectures and demonstrations, and major exhibitions.

Remembered as one of the PMW's most prestigious exhibitions is Prints from New York: Contemporary Images from the Printmaking Workshop, held at the Museum of the City of New York between 15 September 1981 and 1 January 1982. Commenting on that exhibition, Steven Miller, the curator of paintings, prints, and photography for the Museum, accurately summarized the importance of the PMW. "As an umbrella to a great variety of people and ideas, the Workshop is reflective of New York City. In a field of considerable innovation and activity, the Workshop serves as a funnel, repository, and catalyst, passing on the know-how of one generation to the next."

Blackburn's mission continues today under the auspices of the Elizabeth Foundation. A broad range of printmaking classes and exhibitions are open to enrollment.

-

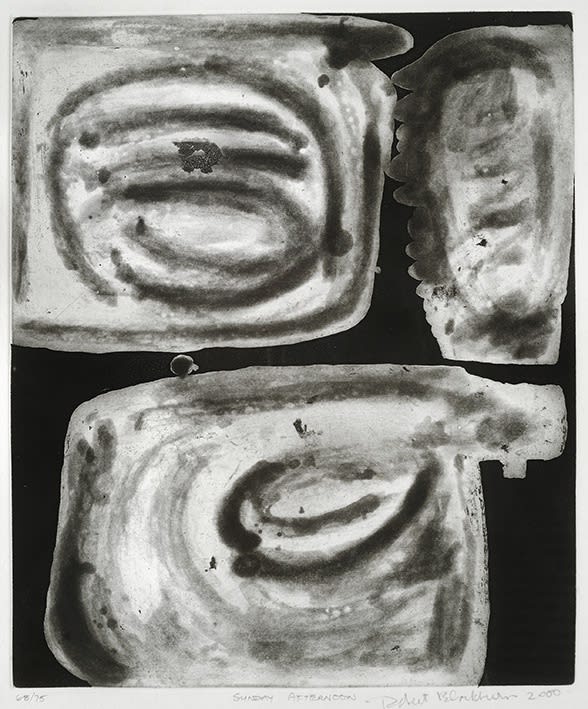

In his later years, Blackburn took advantage of the many invitations he received but very often handed off to others. In 1989, he spent time at the Fabric Workshop in Philadelphia, completing three large gesturally abstract stretched-linen works. In 1992, Blackburn was awarded a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship. He poured the money he won directly back into the workshop. In 2000, Dieu Donné Papermill in New York welcomed him to create prints. Although Blackburn had long been a collaborator and advisor, the etching Sunday Afternoon was the first work he made there. This same year he was awarded a Lee Krasner Award from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.

-

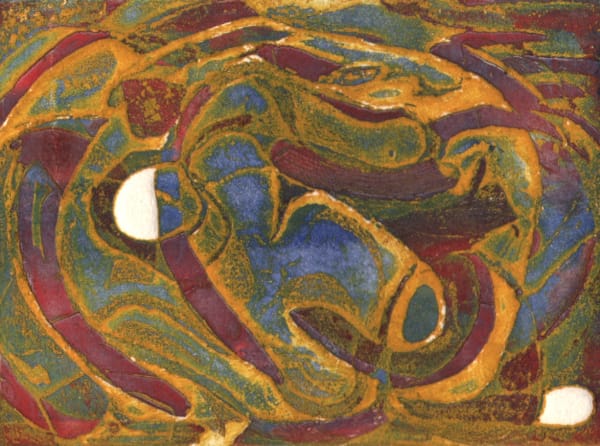

Bob Blackburn’s decades-long friendship and trust in Kathy Caraccio's ability led to the series of viscosity mono prints, which form the final prints project in Blackburn’s oeuvre, Organic Things (2001). It is another case of Blackburn revisiting an earlier project. The zinc plate was engraved and etched in 1979, and a few impressions were pulled with the titles Forms and Experiment. Guiding Kathy with her deep knowledge of printing color viscosity, 30 unique impressions were created, each with its unique color solution ranging from soft, pastel shades to deep, vibrant reds, yellows and blues. Blackburn’s trust in his philosophy and history repaid him very well, and we are extremely proud to share four examples that show the versatility of the viscosity method, each revealing a fresh and informative response to the structure inherent in Blackburn’s deeply etched plate.

-

Blackburn's generosity paved the way for many artists, and we suspect many of them may not have had an opportunity to make the prints we are honored to share here without the availability of his wisdom and drive to keep his Print Making Workshop functioning at a very high level. His career experiences span many significant moments in 20th-century American art history and Blackburn's contribution serves to move that story forward on many fronts. While his impact is so clearly an American phenomenon, Blackburn's influence reached around the globe. That his printmaking practice took second place to the Workshop does in no way diminish the significance of what he made, and, as the examples included here demonstrate, his contribution as an artist is sound and well worth celebrating.