-

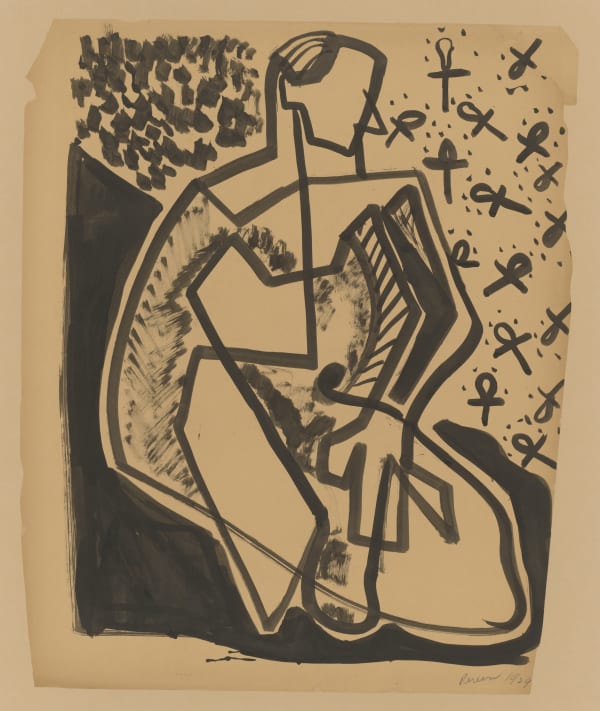

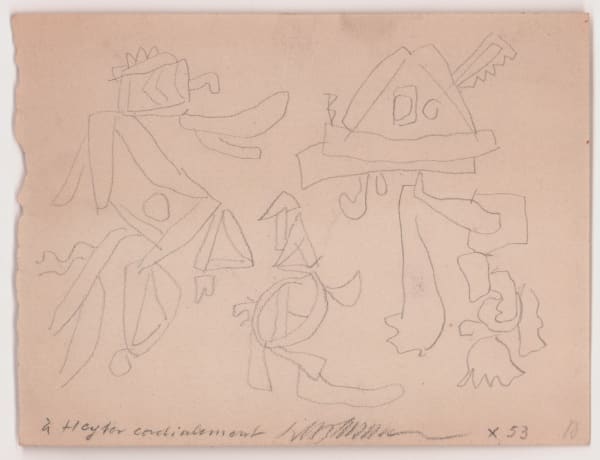

Manhattan, 1929: Irene Rice Pereira clocked out of her day job as a stenographer and grabbed a quick bite on her way to 215 W. 57th Street for a figure drawing class with Jan Matulka, professor of painting and drawing at the esteemed Arts Students League. One of those productive evenings, with a decisive and confident hand, she created this ink drawing. It walks the line between abstraction and representation, hinting at what's to come. Pereira’s importance to the development of Non-Objective Abstract painting in America is paramount. This early drawing shows an artist embracing abstract thought, pushing the boundaries of what's possible, and truly enjoying the process. The figure is contained within its own space, separate from the background, and is composed of a neo-cubist structure. It will be almost another decade until Pereira breaks through to Non-objective abstraction.

Twenty years prior, Charles C. Dawson was the first African American student to attend the Arts Students League. Due to the abhorrent racism he faced there, he made his way to the Art Institute of Chicago, where he was welcomed. His career mirrors that of Dox Thrash in many ways, and in 1917 Dawson enlisted in the American Expeditionary Forces in France, later known as the Buffalo Soldiers. After WW I, he returned to Chicago and became an important member of the city's Arts community, co-founding Chicago’s first Black arts collective, the Arts and Letters Society, and establishing the Chicago Art League. In 1927, three of his paintings were included in the first exhibition of African American art at the Chicago Art Institute. He distinguished himself as a commercial illustrator while upholding a devoted studio practice. In the 1940s, Dawson became the curator of the Museum of Negro Art and Culture at his alma mater, Tuskegee University in Alabama. We are delighted to share an early watercolor by Dawson, an idyllic tropical scene of masterful technique. A bold yet simple design employs silhouetted vines and palm fronds to frame and direct our eyes to the delicately painted yet exuberant dancers. Don’t miss the parrot.

-

Paris has long been a magnet for forward-thinking, artistic-minded souls. Drawing people from all over the world who have their finger on the pulse, and many of the artists included in our presentation have spent significant time there. The city's impact on the development of Modern Art is undisputed and Montparnasse, in the 1930s, was where you wanted to be. At 17 rue Campagne Première, on a little cobblestone street just off the Boulevard Raspail, was the locale of an experimental printmaking workshop that would become the epicenter of new, radical art and a hub for intellectual and political discourse. This was the second location of the groundbreaking Atelier 17 and its namesake.

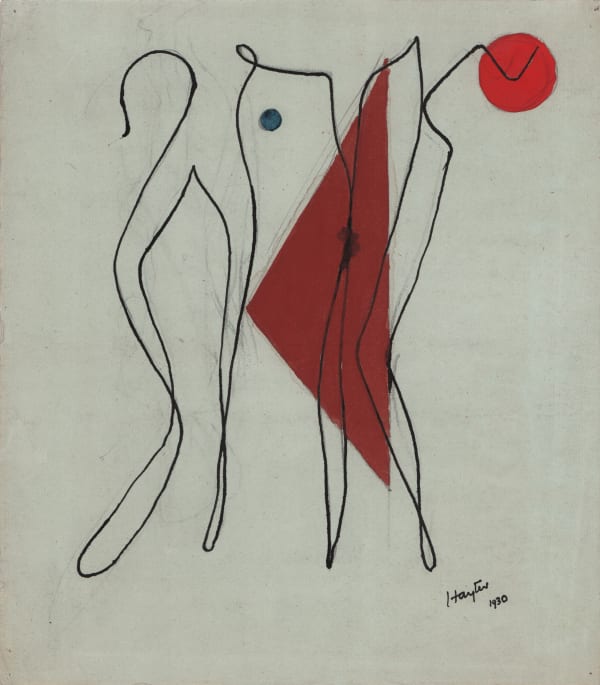

In 1926, Stanley William Hayter left Abadan, Iran, where he had been working as a chemist for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, and started a new career as an artist in the bohemian art capital. Paris - the polar opposite of the desert, was unbelievably beautiful and culturally rich. Hayter was attracted to the spirit of this potent city, which fueled his art and life, and he wasn't alone. Gabor Peterdi, a Hungarian prtotegè, arrived in 1931 after winning the coveted Prix de Rome the year prior at the tender age of 15. He first encountered Hayter and began making engravings at Atelier 17 in 1933. He quickly mastered the technique of engraving, which would remain the foundation of his printmaking practice. John Ferren visited for the first time in 1929, and promptly returned the following year, where he remained for almost a decade. Ferren produced his first plaster prints under Hayter’s watchful eye. These three artists began a close friendship that continued throughout their lives and across continents. They would often trade works of art and share in each other's discoveries - this Ferren watercolor comes out of Peterdi's personal collection.

When city life became overwhelming, artists, like many of us, would retreat to the seaside. The Mediterranean coast in the south of France provided much-needed relief from the stresses of urban life. Hayter made his 1928 pastel sketch of a fortress-like structure at a bend in the road in St Tropez. It shows a command of solid form and structure. He masterfully captures the mid-day light, casting strong shadows that define architectural elements. Time away from urban life provided space for reflection and reconsideration of one's practice and acted as an unconscious pitstop and refueling station for the forthcoming revolution in style.

-

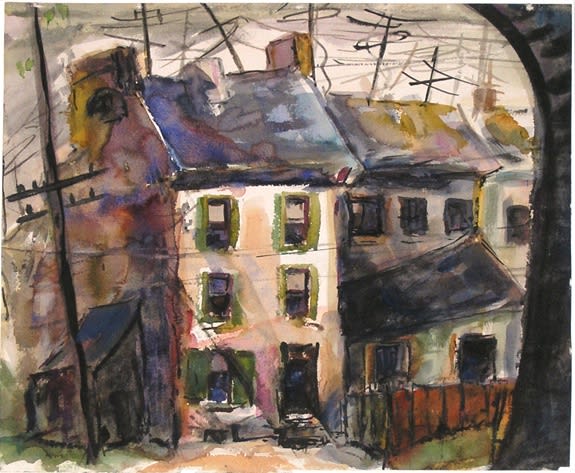

These two interior scenes by Morris Blackburn and Benton Spruance reflect intimacy - a peaceful moment to remind the viewer that one does not have to travel far from home to find inspiration. They are also very fine, early examples of American Modernism. Modernism, as developed in Paris, began making appearances in the US in the 1910s with the Armory Show and exhibitions organized by Alfred Stieglitz. Blackburn and Spruance, students at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the 1920s, won scholarships to travel to Europe, specifically Paris where both young artists studied at the Académie Julian. New ideas and experiences traveled back to their studios in Philadelphia, and each established impressive careers as progressive artists and educators, infusing their academic training with Modernist concepts. Later, in the mid-1940s, both artists met at The Philadelphia Print Club, where weekly workshops led by Hayter were established to share the innovations of Atelier 17. Blackburn and Spruance thoroughly embraced the opportunity, and their art-making practices expanded accordingly.

The rise of fascism in Europe in the mid-30s was the beginning of a great shift as the nucleas of the avant-garde moved from Paris to New York City. Before WW II, Paris reigned supreme and was the epicenter of the contemporary art world. The dire realization of a war on the horizon led to the corresponding uprooting and relocation of many European artists and intellectuals. As a result, the American metropolis began to gather momentum as the center of an ever-changing art world moved west to New York City. This attention to the American scene brought excitement and pressure for American artists to establish their own forms of art distinguished from the prevailing European innovations.

Fascination with the phenomenon of American cities that began in the 20th Century continues to this day. Humans rejoice in the ideals of uniting to build better lives for themselves. Artists’ response to changing urban environments has long been part of the romance of changing skylines and the stage-like nature of city streets.

Earl Horter and Harold Rudolph worked with both themes, drawing a contrast between very tall buildings and relatively diminutive people on the streets. Horter’s drawing contrasts a skyscraper still under construction with small figures and a sailboat in the foreground. Rudolph’s New York nocturne plays on the saturated blue of the night sky; the tower, 70 Pine Street in lower Manhattan, is lit like a beacon, drawing our gaze upward from the shadowed streets with cars in silhouette. The drawings and watercolors by the great African American artist Dox Thrash indicate urban issues still relevant today—suburbanization and gentrification are not new. The cycles of urban renewal are not without impact on people marginalized by tremendous changes to urban environments.

-

The Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), created to provide relief to artists during the Great Depression, provided an opportunity for those whose works were previously not seen in mainstream art venues. More than 10,000 artists were hired, and women, recent immigrants, and African American men became part of art-making communities as never before. The very changed demographics added new visions and voices, stretching the definitions of Modern art.

Philadelphia’s WPA projects included one of the few stand-alone print-making workshops in the USA. Claude Clark and Dox Thrash were among the core of African Americans employed by the WPA and worked diligently to establish notable careers.

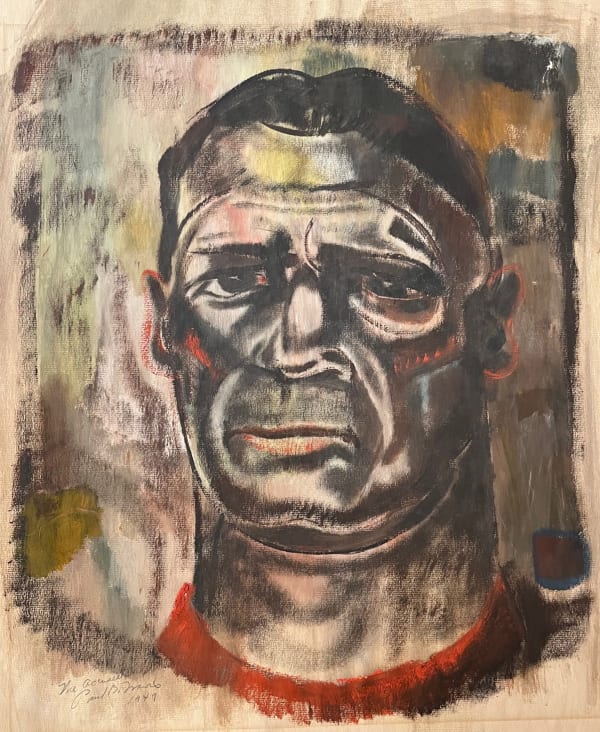

The Modernist portrait serves a new function, giving powerful images and visibility to faces previously omitted. Denying people of color and women a place in our art institutions was beginning to be replaced with inclusion.

-

Surréalisme made its American debut with Chick Austin’s Newer Super-Realism exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in November of 1931, Julian Levy organized a similar exhibition at his gallery the next year, and in December of 1936, Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, curated by Alfred H. Barr, opened at the Museum of Modern Art. That same year, and just two years before coming to the USA, Stanley William Hayter assisted in organizing the International Surrealist Exhibition, Burlington House, London, the first Surrealist exhibition in London. By the late 1930s, names like Dali, Ernst, and Masson were entering into everyday conversations among progressive-minded artists. These radical Surrealists were gaining respect and began to be sought after by major art institutions and private art collectors. Younger artists were stimulated by this wild, new trend, and students began consuming and digesting surreal ideas. Leon Kelly, Fred Becker, Francine Felsenthal, and William Fett, all embraced Surrealism in their work from this period. California School of Fine Arts professor Ralph Stackpole taught sculpture to a young Helen Phillips, who would go on to embrace automatism and surreal interests in ethnographic art and style. Theodore Stamos, like many Abstract Expressionists, first worked through Surrealist ideas in a semi-representational style before embracing a purer, complete abstraction by the 1950s. Jimmy Ernst was a direct disciple of Surrealism and continued in his father’s footsteps.

-

The effect of war on the human psyche is most evident in Surrealism and Dada art, and these art movements are the direct and apt response to World War I, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II. Many artists from this period enlisted and faced combat witnessing unimaginable atrocities. Years later, some of these soldier-artists suffered from undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder. Drawing became a therapeutic release. André Masson fought in WW I and was severely injured, leading to a lifelong physical and psychological impact. Julian Trevelyan served as a Camouflage Officer and was a member of the Royal Engineers from 1940–43, serving in North Africa and Palestine. Fred Becker worked on the assembly line for the Republic Aviation plant and in January of 1944, took a position with the Office of War Information which sent him to India and China for one year.

-

The first wave of American Abstraction developed during the 1910s when preeminent artists living abroad were influenced by the development of abstract painting in Europe and brought these new ideas back home to a cautious but curious American public. By the 1940s, a second wave of abstraction developed when a new generation of vanguard artists, with a well-established foundation of modernism (taught to them in art schools throughout the country), began mixing with the recently transplanted Surrealist artists who put their faith in automatism, free-association, and creative anarchy. This, mixed with some good ol' bravado, created a uniquely American art, stemming from but severing completely from European influence.

Clubs were formed, manifestos declared - leading to all-night debates over the esoteric differences between non-objective painting and figurative-based abstraction - passionately argued by both sides. The American Abstract Artists, the 8th Street "Club," the Arts Students League, Atelier 17, and the New School for Social Research became meeting grounds for lectures, debates, and even protests. These conversations would continue at the local pubs or late-night loft parties, often leading to breakthroughs in one's art practice. In nearby cold-water studios, artists began the arduous journey of bringing abstract thought into action. Although the American public remained skeptical, Abstract Expressionism was taking shape, and this new, New York School was making a significant impact and gaining notoriety.

-

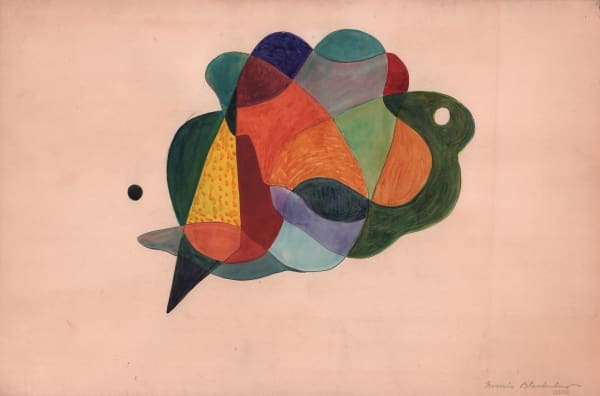

Equal to Jazz, the innovative and improvisational music of the 20th Century, Abstract Expressionism was unequivocally American. By the 1950s, it was gaining worldwide attention and affirmed New York’s role as the center of the art world, raising the profile of American art to a status it had not previously enjoyed. Sue Fuller's lively composition, Boogie Woogie of 1946, is a superb early example of this new style. With a pulsing rhythm of bold color and interconnected shape, this gouache on paper explodes with positive energy and celebrates life. The complicated structure wiggles and bops to the beat of a post-war America, a sign of optimism and hope for the future.

-

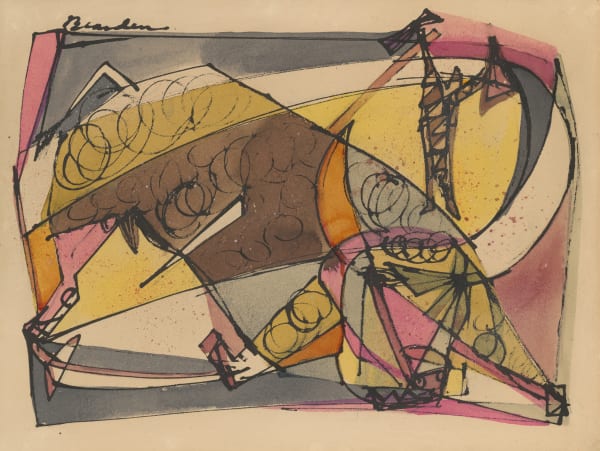

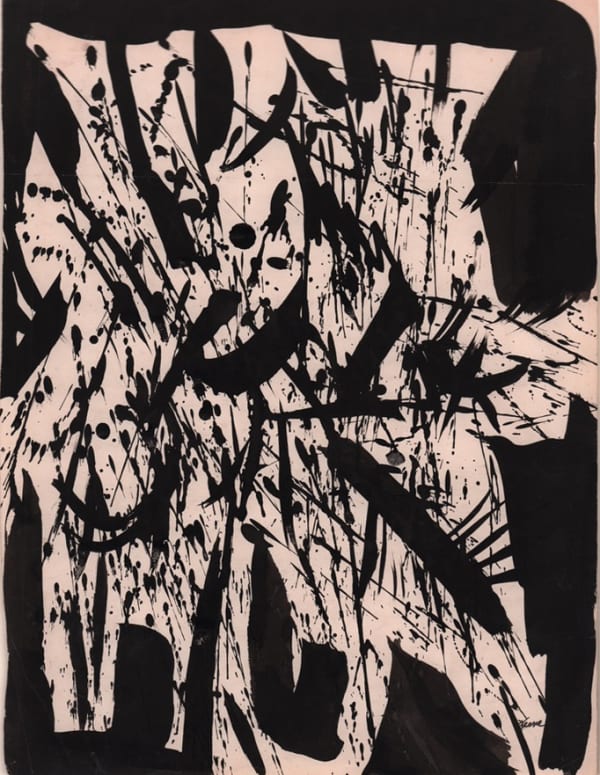

These two works on paper by Dorothy Dehner and Norman Lewis speak to one another. With heightened attention to materiality and mark-making, they achieve real emotion and consideration for their abstract motifs. Working abstractly, both artists find a strong affinity with their choice of basic drawing materials—watercolor, graphite, ink, and oil paints evoke a powerful experience; carefully looking at these works repays us handsomely.

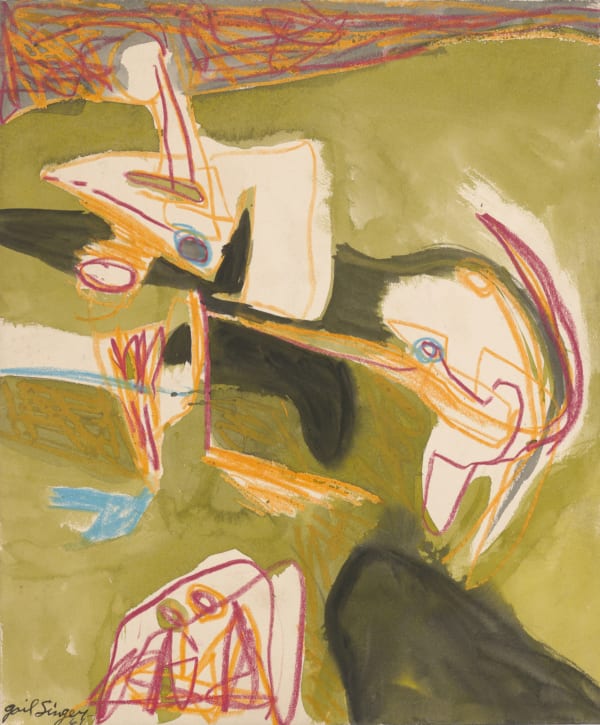

Gail Singer brings a frenetic, high-key energy to her drawings and prints. The upended compositions are truly unique and entirely her own. Singer brings a sense of raw emotion to her work, and her ability to harness a variety of media on a single sheet astonishes. Ink, crayon, and watercolor are at one with her intent, and it feels as though Singer assigns each mark made a role that can only be played with the media of her choice. Born in Texas, she studied with Fred Becker at Washington University in St. Louis and first visited Paris in 1952 on scholarship. She found an empathetic community among the artists working at Atelier 17 and remained abroad for the rest of her life.

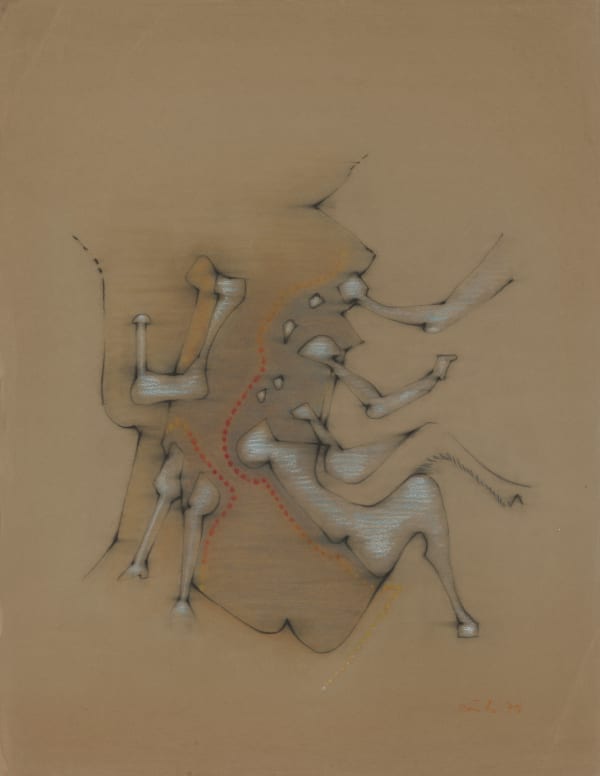

We enjoy looking at Gail Singer's work with Enrique Zanartu's gestural abstraction made in 1954. Born in Paris, his family returned to Chile in 1938. Zanartu began working with Hayter in New York in 1944, where he established a distinctive approach to etching & engraving. Zanartu relocated to Paris in 1950 and directed Atelier 17 until 1957. He and Singer shared similar concerns in their drawings, and a close look shows Singer embracing pure gesture while Zanartu retains information of the figurative impulses that inspire his exceptional works.

-

Beauford Delaney moved to Paris in 1953, where he continued to develop his abstract style focused on color and light to communicate strong emotions. This pair of paintings on paper were made with the same palette of bright colors set against a darkened background. They convey a deep understanding of synthesized light and the tactile nature of paint Delaney achieved, and the importance of nature as a jumping-off point for his abstraction.

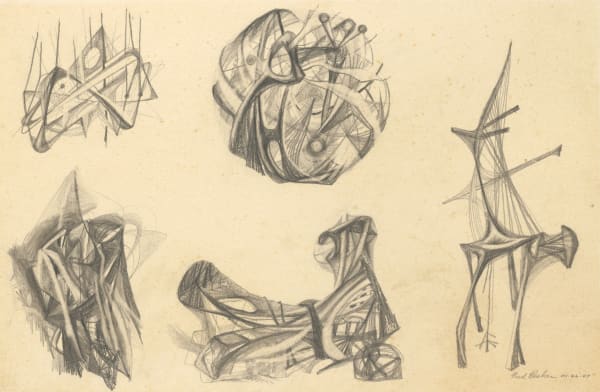

Paul Keene, Maria Helena Viera De Silva, Gabor Peterdi, Terry Haass, and Enrique Zanartu draw inspiration from their love of nature and expeditious demeanors. World travelers, the always-changing landscapes they experienced inspired color choice, movement, and form. Filtered light coming through the leaves of a fruit tree bounces off each other in Peterdi's watercolor of 1958. Shards of light clash against each other like tectonic plates in Terry Haass' groundbreaking pastels of 1965. Viera De Silva's ink and watercolor drawing plays on the scale and reads as both a field of black line that filters the light within or a vast imagined landscape space. Paul Keene's Landscape of 1964 is a loose interpretation of land and sky and an intuitive sense of place. -

There always have been artists working in opposition to the popular trends of their day. The ubiquitous nature of post-war abstraction may cause us to overlook the many artists who blazed their own trail, speaking in different tongues or dialects and yet no less part of the ever-evolving language of visual art; artists such as Paul Keene, Jerome Kaplan, Robert Gwarthmay, Norma Morgan, and Bob Thompson. The endless number of ways WW II impacted the industrialized world meant that life as it was known before the war had changed forever. Humanness has changed, and so with it, the way our human forms are depicted in art. The social and political climate throughout America in the 1960s and 1970s, with a new emphasis on pop culture, televisions in every home, and over-consumed mass marketing - all fueled artists’ need to reinvent their forms and subjects. Here we include works united by their makers’ choice to create in clearer terms, using their skills to tell us about their experiences.

-

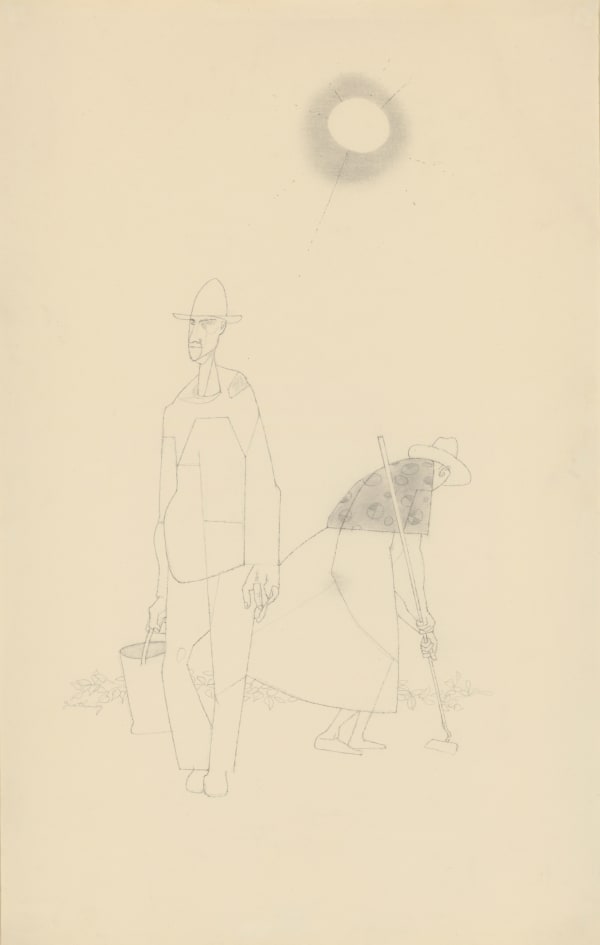

The 1980s brought a celebrated return to figurative content in art, a kind of neo-expressionist response to Minimalist and Conceptual art. Hayter and Fett never completely abandoned figuration and their works on paper hold vital responses to the creative instincts and impulses that served each artist so well over their long careers. Seeing these long-time friends remain true to their rigorous studio practice is gratifying. Spatial and tonal complexity distinguishes the very late works, and these lively examples speak to the verve nurtured over the decades. Both artists synthesize color in remarkable ways, seeing the world and absorbing what is new in the art around them. The two works by Hayter show him deconstructing ideas that make his late work so exciting, while Fett has arrived at ways of simplifying his landscapes with figures inspired by his beloved Mexico.

-

This selection of Modern works provides a splendid opportunity to look at 20th Century works on paper not just with hindsight, but hopefully with a wider, more inclusive lens. The story of Abstract Expressionism, like Surrealism before it, was essentially made out to be an all-white, male-only phenomenon. We now know many extraordinary women artists and artists of color were very much part of the scene if, in fact, disregarded and given few opportunities to showcase their work. We delight in celebrating their accomplishments. We feel honored to bring much-needed attention to artists whose works were often overlooked and underappreciated. Gail Singer, Terry Haass, Jean Morrison, Minna Citron, Sue Fuller, Enrique Zanartu, Bob Thompson, Sam Brown, Charles Dawson, Dox Thrash, Paul Keene are very much part of the story of American art and we hope you’ll enjoy our approach to expanding the narrative with eyes wide open to new considerations. The unique perspectives of these artists show an ingenuity and a curiosity we embrace and delight in sharing.